Image Source: www.theguardian.com

It was a week for football's golden oldies. Samuel Eto'o, at 33, deftly opening the door against Galatasaray and Arsenal and Ryan Giggs, at 40, adding calm and class to Manchester United's engine room against Olympiakos. Arsène Wenger, at 64, chalked up his 1,000th Arsenal game in a daytime "nightmare" at Stamford Bridge.

Amid the eulogies for Wenger, John Hartson spoke of his methods "putting another two or three years" on the careers of Tony Adams, Lee Dixon and Ian Wright. Few would dispute that. In the past decade, those methods have become football's methods. Players are fitter. They recover from training with finely tuned protein-carb shakes, ice baths and massage; not a swift one-two at the pub.

We have come a long way from the days when footballers regarded broccoli as that guy who produced the Bond movies, and only did a downward dog when they slid off a bar stool.

Last year Sir Alex Ferguson said that "sport science is the biggest and most important change in my lifetime". Manchester United monitor 29 variables that may increase a player's susceptibility to injury; sometimes players will be pulled out just before training because something in their data isn't right.

Given such widespread advances, you might expect the average age of players in Europe's top leagues to be climbing sharply. It is not. The Football Observatory recently compared the average age by position of players in the Premier League, Serie A, La Liga, Bundesliga and Ligue 1 from 2005-06 to 2013-14 and found it was also static.

The average age of a first-team defender in the big five European leagues in 2005-06 was 26.21 years; now it is 26.35 – an increase of 0.14 years. The figures for goalkeepers, midfielders and attackers have barely changed either.

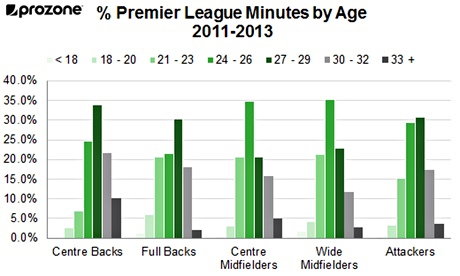

Meanwhile in the Premier League, Prozone's data for the 2011-12 and 2012-13 seasons shows that full-backs 33 or over played just 2.0% of all minutes played by full-backs. For wide midfielders that figure was 2.7%; strikers 3.6% and central midfielders 4.9%. For central defenders – whose positioning can sometimes negate a lack of pace – it was higher at 10.1%.

Image Source: www.theguardian.com

So what is happening? Two things. Sports science is helping older players to stave off the effects of ageing. But, at the same time, the physical demands on footballers is far greater too. So the status quo prevails. Once footballers hit their early thirties they are on borrowed time. Just like they always were.

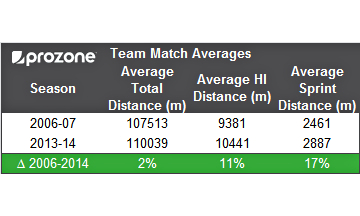

What is striking, though, is how much faster football has become in the past decade. TV commentators in the 1970s and 1980s were fond of talking about matches being played at 100-miles-an-hour. It was a Sunday morning pootle compared to today's game.

Image Source: www.theguardian.com

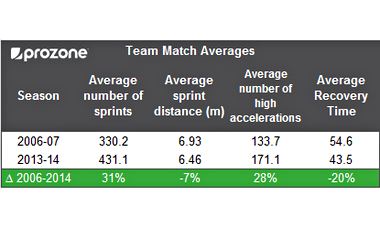

In 2006-07 the average number of sprints per team in a Premier League match was 330.2. This season Prozone's data show that it is 431.1, a 30.6% increase. Meanwhile recovery time between high intensity sprints (speeds of greater than 5.5 metres per second) has dropped from 54.6 seconds to 43.5 seconds, a decline of 20%.

Dr. Mary Kneiser’s nearly 20 years of experience in physical medicine and rehabilitation is decorated with various awards and recognition for her skill and expertise in patient care. Get a glimpse of her highly respected practice by visiting this blog.

Image Source: www.theguardian.com

Perhaps it is not surprising there are so few full-backs, wide midfielders and forwards over 33. They play in positions where a dip in pace is more likely to affect performance. It is not only in road safety adverts where speed kills.

Another development is that clubs monitor GPS and heart-rate data in training. They usually know when a player is 'gone' before we do.

The growth in post- and pre-season tours may also be a factor. Players have less down time to recover in the off-season – so recovery time, which becomes more important with age, can be scarce.

Of course the rate of decline will vary. Genetics, lifestyle, injury history and the number of games can all be a factor. But players are battling against age earlier than is often assumed. Maximal aerobic capacity – or V02 max – peaks around 18 to 20 and while it can plateau until 25 it tends to then decrease by approximately 8-10% per decade.

Dr James Carter, the head of the Gatorade Sport Science Institute at Loughborough University, says that vigorous training after the age of 25 can limit that decline to around 5% per decade but "significant reductions in physiological and performance-related capabilities will be more pronounced once a player enters their thirties".

With some players physiology is not everything. Even in his final season, Paul Scholes's passing figures were as good as ever. Others make themselves relevant in fresh ways. When Giggs still possessed the acceleration of a Maserati and the hips of a ballroom dancer, the ball was lover to nuzzle on those jinking, parabola-like runs; now it is more of a passing acquaintance.

But as a general rule, improvements in sport science and medicine have benefitted younger players as much as older ones. And so veterans are better retained at a similar rate than they were a decade ago. As Carter reminds us, "extending the shelf life of footballers beyond 35, in most cases, is still beyond the remit of science, technology and best practice".

When Giggs and Eto'o started out, football was considered a young man's game. Despite their notable achievements in the past week it still generally is.